The COVID-19 pandemic is a major crisis that will continue to pose a significant threat to the entire global community. To mitigate its lethal effects, unprecedented social distancing measures have been implemented by governments to slow the rate of infection and save lives, with many governments partnering with technology businesses to enable intelligent, real-time interventions.

Read next: Surveillance: Readying for the Seismic Shift

For example:

In China, a massive state surveillance programme has been implemented, gathering people’s smartphone app data in combination with real-time analysis of body temperatures, GPS locations, satellite imagery, facial recognition, drone monitoring and even data from individual biometric bracelets. All this data is being fed into state-controlled centralised databases for further analysis to understand behaviours and infection spread;

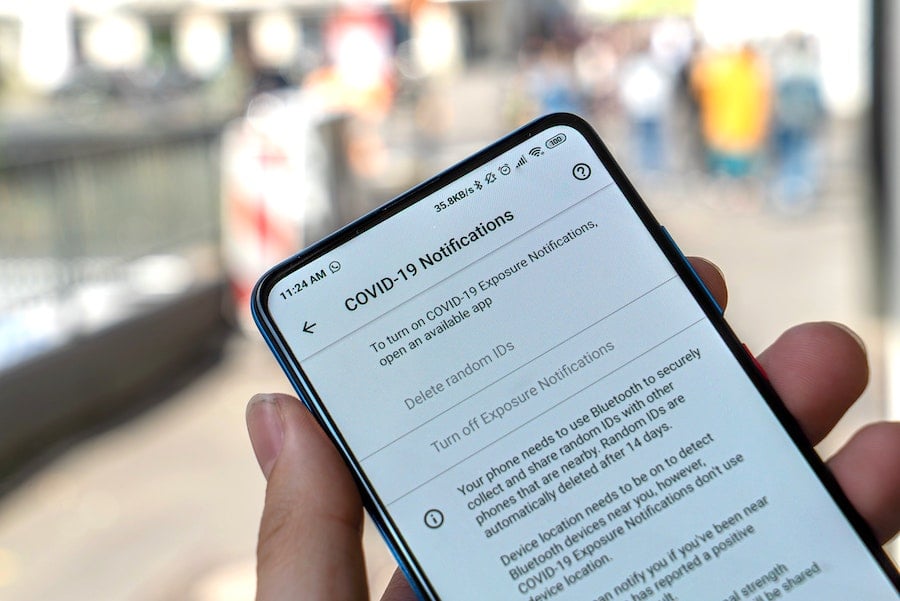

Australia has launched its “COVIDSafe” application for contact tracing, using Bluetooth technology to trace every contact citizens may have had with and others that have tested positive for the virus (for those using the app). This allows the government to analyse the frequency & density of contact with confirmed carriers and upload this information to state servers for use by health authorities and emergency response teams.

There is no doubt that such measures are a hugely powerful tool in the fight against the virus. An analysis of Daily New Cases in Australia shows just how effective these measures have been:

To be able to do this however, governments are executing data collection and analysis at breath-taking speed, performing actions that would normally be frowned upon or deemed unlawful in normal times. This raises an important question: how far should governments and other organisations be allowed to bend the rules of data privacy, security & consent in order to save lives in times of crisis, and how should ethical risks be managed?

The ethics of data in pandemics

Governments and their citizens are acutely aware of the ethical dangers related to mass surveillance, demonstrated by the mixed reaction across different countries and the varying attitudes among governments to the adoption of intelligent surveillance measures. This culminates in several difficult questions for today’s modern societies:

What exactly does it mean to be “ethical” with data when lives are at stake?

What are the expectations of citizens with respect to these measures, especially to controversial ones?

How do you maintain a consistent approach in the face of enormous geographic & cultural variation?

To answer these questions, we need to consider the ethical risks associated with data during such crises. Here, we have identified five main areas of ethical risk and why governments and other organisations should consider them.

1. State-level surveillance

The pandemic might normalise the deployment of mass surveillance tools in countries that have so far rejected them. As explained by Yuval Harari in a recent article on the topic, this could signify a dramatic transition from “over the skin” to “under the skin” surveillance, with technology used to monitor citizen biometrics 24 hours a day and government algorithms used to screen & categorise citizens in real-time. While such measures would certainly help to manage a major pandemic, it would also give legitimacy to new surveillance systems that would curtail basic human rights.

2. Misuse of personal data

Data collected from citizens with specific consent rights for the virus could be misused for other purposes; particularly when combined with other data sources that might already be available, such as financial data. This could include developing AI systems to monitor behaviours. Given the power of these data sets, it could be used by unethical regimes to influence popular thought for political gain, or by private companies for financial gain.

3. Lost lives from inaction

Adhering to the strict data privacy regulations (such as GDPR) may prevent governments from operating at the speed and scale required to help the very same people these rules were initially designed to protect. This may result in significant loss of life if these restrictions prevent governments from taking immediate action. Governments will need to weigh-up compliance and ethical & regulatory requirements against the potential for saving lives.

4. Extended data lifecycles

Whilst temporary measures may be put in place for an immediate emergency, such measures normally have a habit of outlasting the emergencies for which they were introduced. Even when infection rates are down to zero, governments and organisations may justify the need to keep surveillance and personal data collection in place. This also extends the lifecycle of the data and increases the risks of it falling into the wrong hands.

5. Sub-optimal or biased decisions

Given the wide-spread adoption of AI to manage decision making on large datasets, there is a risk that models deployed at scale could inadvertently embed discrimination and unfair biases into government decisions. This could result in certain geographies or segments of society being put at greater risk or unfairly treated during the government response. With smartphones being the key data collection tool for monitoring initiatives, societies where smartphones are less prevalent may well be miss-represented in models and the resulting Covid response, with potentially life-changing consequences. Adopting ethical principles for data

Given the nature, scale & impact of data ethics risks, as well as the varying cultural and historical attitudes towards measures that give rise to them, we recommend that governments adopt a principle-based approach to guide their decisions and actions with data.

Principle 1: Accountability for decisions

The risks & decisions related to data ethics should have clear accountability across all parties within the value chain of data & analytics, ensuring that potential liabilities are identified, understood, and proactively managed.

If ethical breaches should arise, the decisions made to resolve them should be clearly documented and the policies used to inform them consistently defined and made available for risk & internal audit oversight. All AI systems should be built with auditability and accountability in mind. Individuals or teams responsible for algorithms should be identified as part of its documentation and changes managed in a collaborative, transparent manner.

Principle 2: Organisation-wide ethical oversight

Senior management should drive data ethics and ensure that it is adopted across functions by building it into their existing governance frameworks. Roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined and understood for Data, System & Model Owners within development teams. Robust processes and procedures should be in place to ensure models are documented and maintained by those involved in the use of data.

As an example of this principle, the Australian government has as published a privacy impact assessment to ensure risks are addressed throughout the development of its app COVIDSafe. It has passed a temporary legal framework (to be backed up by further legislation) stating that only health authorities (or those maintaining the app itself) can access the information it contains.

Principle 3: Justify the need for data

Organisations should ensure that individuals understand why data collection is in their interest, making it clear on how the data will be used to drive decisions that keep them safe. While organisations may need to act urgently to collect the data they require, they should ensure that they communicate effectively to keep individuals informed.

Organisations should assume that, if they wish to retain and continue to use personal data beyond the initial crisis, they will need to make the case to the affected individuals and clearly articulate the benefits to them.

Principle 4: Transparent, auditable data management practices

Transparency should underpin the way that data is managed, including how that data is stored, shared, and eventually deleted. Organisations should have a full understanding of how decisions are taken with respect to data retention and deletion and should be able to explain these decisions to citizens, auditors, and regulatory bodies.

Organisations should have agreed policies for how personal data should be anonymised when being used, as well as how it should be archived or deleted when it is no longer required. A culture of trust should be established within the organisation through data ownership & governance structures.

Principle 5: Considerate decision-making

Organisations should identify how AI algorithms could negatively impact certain groups, either due to inherent or programmed biases. Procedures should exist to identify and review the risk of bias in datasets and algorithms, as well as how these can be objectively measured, and decisions taken to correct them justified.

Organisations should put in place a framework and regular reviews to monitor and manage mis-modelling and bias. As part of these reviews, it is important that all people handling data in the chain from collection through to insight understand the dangers of bias and how these dangers are to be mitigated.

In a nutshell

The 2013 Edward Snowden case exposed how government surveillance measures can create distrust between citizens and governments, resulting in new legislative frameworks to address ethical concerns. Governments need to respond urgently to pandemics, but they also need to consider how the methods used to do so will shape the world for years to come, especially in terms of the precedents they establish for data collection and privacy.

To quote Yuval Harari, “When choosing between alternatives, we should ask ourselves not only how to overcome the immediate threat, but also what kind of world we will inhabit once the storm passes. Yes, the storm will pass, humankind will survive, most of us will still be alive — but we will inhabit a different world.”

Contact Us

Ready to achieve your vision? We're here to help.

We'd love to start a conversation. Fill out the form and we'll connect you with the right person.

Searching for a new career?

View job openings